Contents

Use these links to jump to the most relevant part of the guide.

We’ve also made a pdf version which you can download to read at a more convenient time.

The Importance of Strategy

How many times have you considered your product strategy when deciding what to build? Do you even have a product strategy?

We recently conducted some research into the topic of product strategies and how SaaS companies use them as an overall guide.

You can see our findings here.

The quick version of what we found is that the overwhelming majority of businesses (around 70%) are using a Product Strategy when it comes to making important decisions.

Furthermore, the companies who use a strategy report that they are more transparent, employees are more aligned, and that they ultimately make better product decisions. The same companies reported virtually no downsides to creating and using a strategy.

Having a product strategy is vital to making the right product decisions. You can analyze all the data in the world and still end up without any idea of what it means. But when you view the data through the lens of product strategy, then you can focus in on what you need to build.

If you feel like all this talk of product strategy has already left you behind, then not to worry.

This guide is designed to give you an overview of product strategy so that you understand the theory behind it and how you can use it to make product decisions, either for your overall strategy or for one-off projects. It features actionable tips throughout so that you can start working on your own strategy right away.

Ready? Then let’s go…

The Anatomy of Strategy

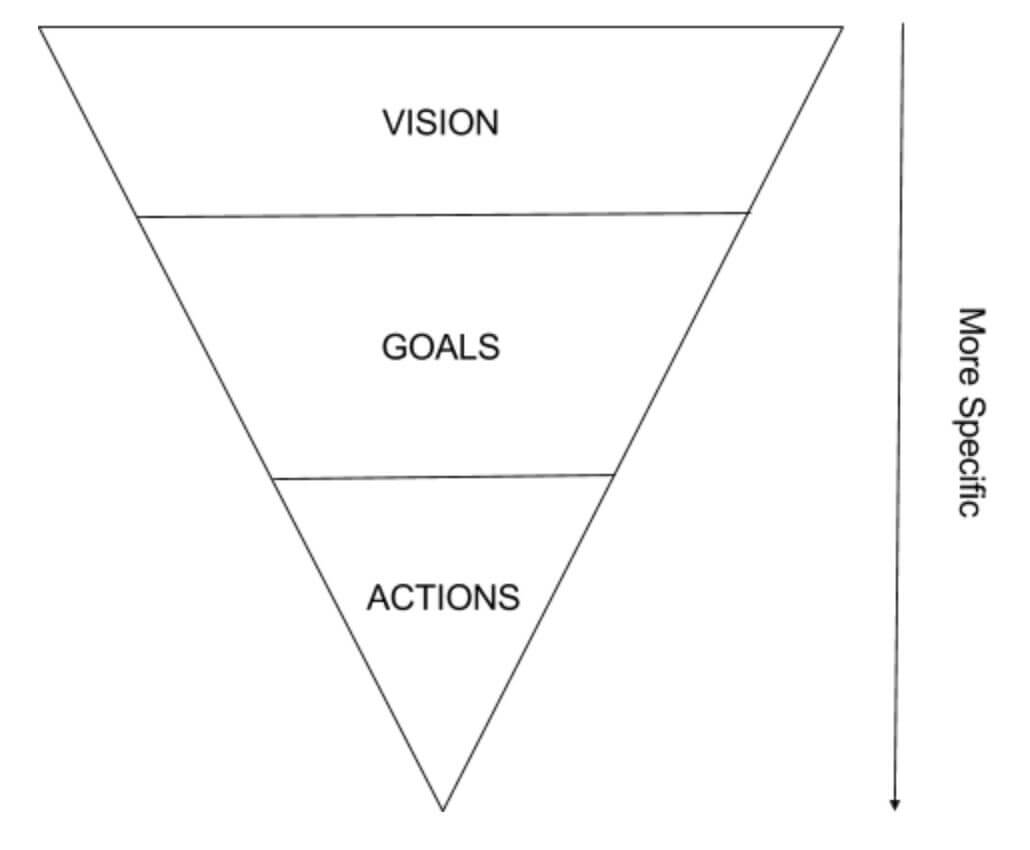

Your product strategy can be broken down into three main components:

VISION → GOALS → ACTIONS

Each of these three are vital to your product strategy, and each takes up a different position in the hierarchy.

Your vision is the overarching idea behind your product. It’s the fundamental force that drives you. Your vision will ultimately dictate any decision you make regarding your product.

Your goals are born out of your vision. These are more specific and act as achievable targets that will help you to fulfill your vision.

Your actions are the tasks you must carry out to achieve your goals. It’s no use setting targets without any idea of how to reach them.

Ultimately, your actions help you to achieve your goals, and achieving your goals helps you to fulfill your product vision.

It is best to view these three components of your strategy as a funnel.

As you move down the funnel, from your vision to your goals to your actions, the funnel narrows and the component becomes more specific. To get to the goals component, you need to go through the vision. Likewise, to get to the actions component, you must go through both vision and goals.

The Funnel in Action

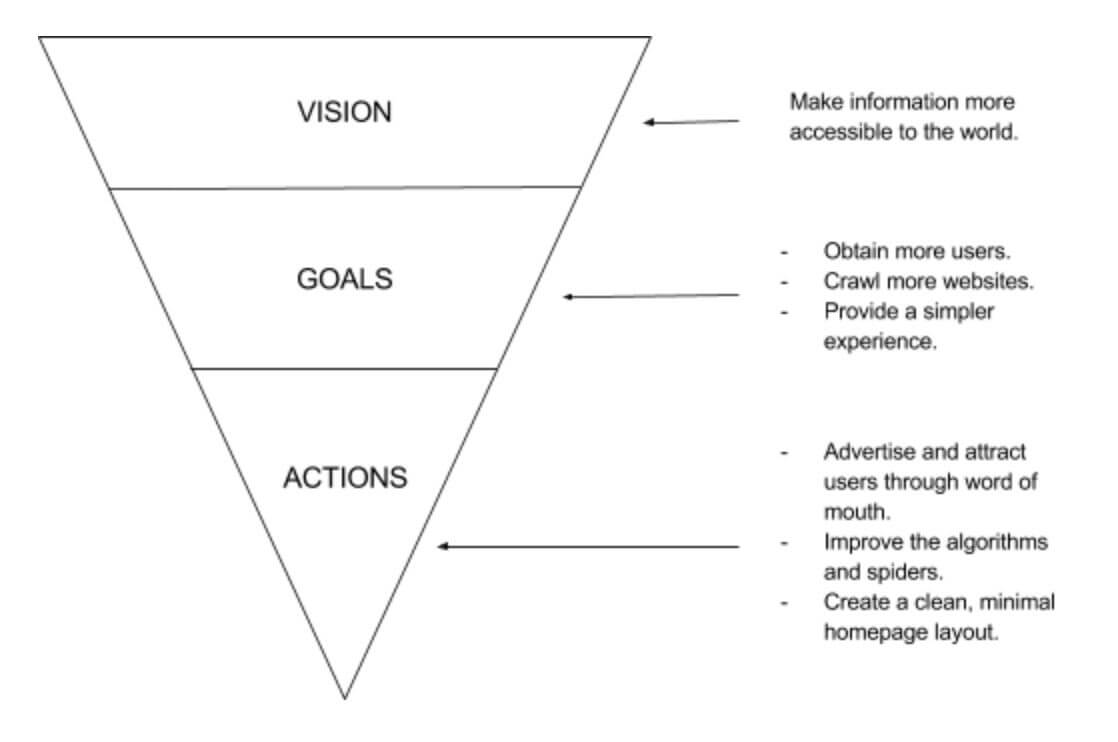

Let’s take a look at the strategy funnel through the lens of an example that we all know well.

When Google first set out to conquer the search engine world, they would have had a product strategy.

Let’s see what their vision might have looked like.

“Google will provide a simple search experience providing people all around the world with the information they desire.”

It’s a bold statement of intent from Google’s founders. It’s also extremely general. How can you even start to measure that?

In order to fulfill their vision, Google set themselves several goals. These goals would have been along the lines of:

G1 - “Obtain more users.”

G2 - “Crawl more websites.”

G3 - “Provide a simpler experience.”

Can you see how these goals are far more measurable that their overarching vision?

By establishing goals in line with their vision, Google were able to find something they could objectively measure their success on. It gave them something tangible to work towards.

Finally, in order to achieve those goals and ultimately fulfill their vision, Google needed a plan of action. Each of their goals would have a corresponding task, such as:

A1 - “Advertise and attract users through word of mouth.”

A2 - “Improve the algorithms and spiders.”

A3 - “Create a clean, minimal homepage layout.”

These actions, when completed, would help Google achieve the goals they laid out. In turn, this achieving their goals would lead to them fulfilling their vision.

Here’s the example added to the funnel diagram.

Hopefully that example has made the structure of a product strategy clearer for you. We’re now going to delve deeper into each of the three sections, including how to generate ideas for each.

Finding Your Vision

You don’t need a crystal ball in order to find your vision. Instead, you need some time and space to think about it.

When your product was nothing more than an idea scrawled on a post-it note, you would have had your vision. It’s the underlying reason for your product’s existence. Trust us when we say you had one.

The trouble is, once your product has been refined and researched and actually becomes something you’re selling, it’s easy to forget what that vision was.

To remember it, you need to think back to the conception of the product.

What were you trying to achieve?

Who were you trying to help?

Why did you decide to make the product?

These questions will uncover the driving force behind your product and the reasons for its existence. The answers to these questions will form your product vision.

So where do you find these answers? Well, in a smaller company, it might be a case of all hands on deck, where everyone chips in with their ideas and opinions. In a larger organization, it may be that the leadership team and the VP of Product have much more sway on the vision.

Our recent survey on strategy found that Product Managers, the CEO, and other C-Level employers were the people most commonly tasked with creating the strategy, and so they’re likely to hold the answers for those questions.

Either way, setting up a meeting to discuss the answers, for everyone involved with deciding on the vision, is a great way to hone them.

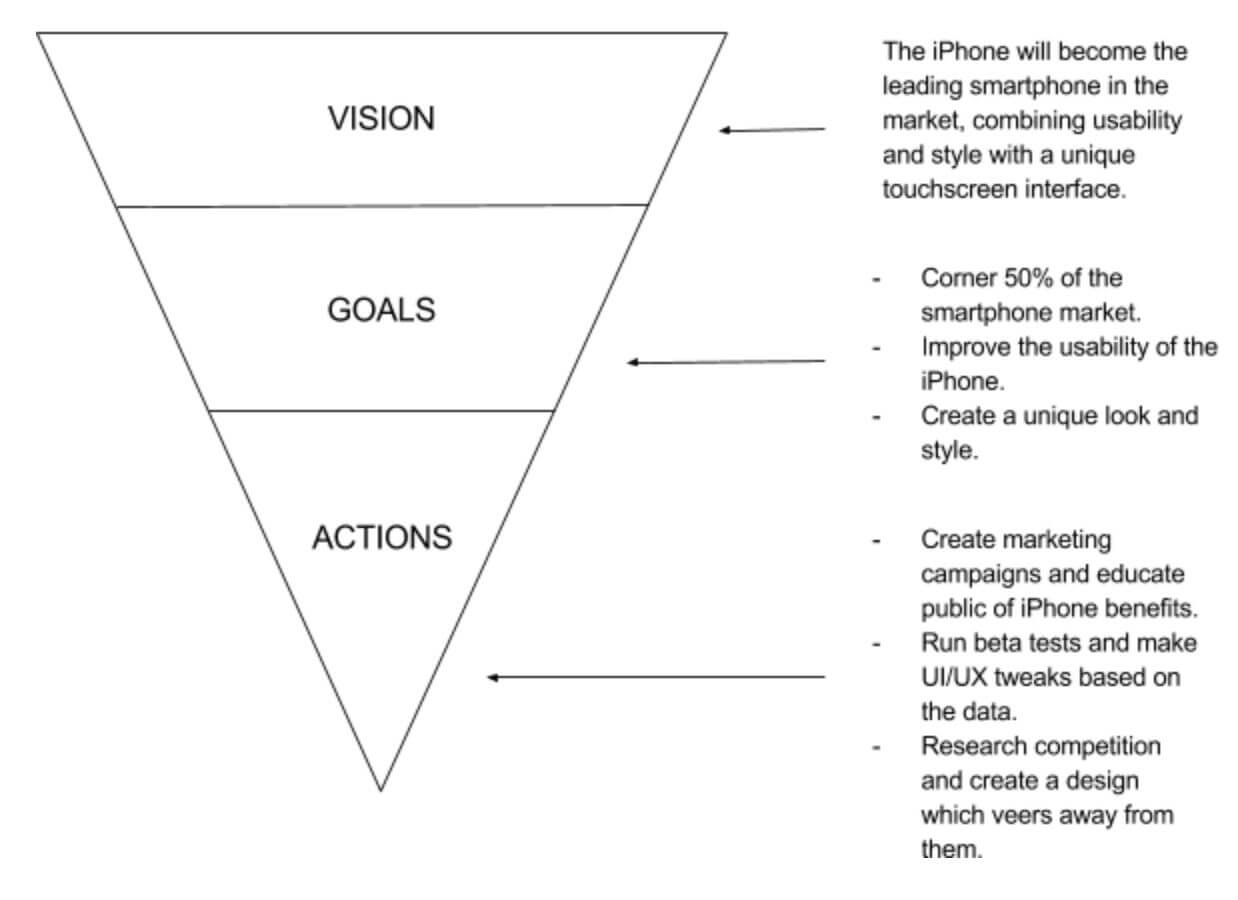

Let’s think of an example. Consider the iPhone. For the purposes of this guide, let us assume that the iPhone was the first smartphone to use a predominantly touch-based means of operation. (While there were other forays into this area, the iPhone was the most popular attempt.)

When Apple first created the iPhone, they would have had a product vision. Let’s see if we can discern it using those questions.

1. What were they trying to achieve?

Well, they wanted to make a smartphone that was more intuitive and easier to use. A touchscreen would be quicker to operate, allowing users to make the most of a smartphone’s plethora of functions.

2. Who were they trying to help?

Before the iPhone, smartphones were a little clumbersome and so only used by those tech-minded enough to persevere with them. Apple’s entry into the smartphone market was designed to help the average person enjoy the benefits of a smartphone.

3. Why did they decide to make this product?

With sales going strong for both their Macbook and iPod offerings, and with smartphone technology rapidly advancing, Apple jumped at the chance to make a smartphone more stylish and usable than what their competition had on offer. Smartphones were not popular at this time and this was an opportunity to make inroads into the market.

By looking at the answers to these three questions, patterns start to emerge. In this example, it appears that Apple wanted to build upon the smartphone by making it easier to use and therefore more attractive a proposition to the public. If you analyze the answers then a vision starts to emerge.

Apple’s product vision for the iPhone could be stated as:

“The iPhone will become the leading smartphone in the market, combining usability and style with a unique touchscreen interface.”

That one sentence encapsulates Apple’s vision for their product. It explains who the product is aimed at (everyone), what sets it apart (touchscreen), and why they wanted to build it (usability).

Your product vision is a statement of intent. It should communicate the core offering and the fundamental reason for your product’s existence. If your product is the what, your vision is the why.

Setting Your Goals

Your goals are a natural progression of your product vision. As explained previously, your vision will inform the goals you set. They have to be compatible.

It goes without saying that if you don’t yet have your vision mapped out, then you can’t possibly set your goals.

The reason for setting goals is that it gives you something to work towards. More often than not, a product vision is something intangible. It is, after all, a vision. It’s an ideology. Goals are a way of fulfilling that ideology.

To set your goals, you need to think about your vision and how you can define it using concrete terms.

Your goals need to be two things: achievable and measurable. There’s no use setting goals that you’ll never achieve. That’s a waste of time and effort. Also, you must be able to measure your progress towards a goal, or else how will you know when you’ve achieved it.

Goals can also vary in length. You might have a few short-term goals (say, over the next quarter) mixed in with more long-term goals (over the next year).

Finally, you need to figure out who is involved with setting the goals. This will vary depending on the size of your organization and the way in which your product teams are structured.

In a big organization, leadership may define the goals. In a smaller company, the product team may set their own. Alternatively, you may come up with vague goals and then narrow them down and make them more specific with the help of the product team.

Let’s return to the Apple iPhone example.

To recap, Apple’s product vision for the iPhone was as follows:

“The iPhone will become the leading smartphone in the market, combining usability and style with a unique touchscreen interface.”

Now, let’s try to break that vision down into specific goals.

One of the obvious goals to come out of the vision is to become the leading smartphone in the market. In other words, they want the biggest market share. A long-term goal could therefore be expressed as:

G1 - “Corner 50% of the smartphone market.”

Can you see how this is both achievable (they aren’t asking for 100%) and measurable (the metrics are defined in the goal)?

Other goals can be pulled out from the vision.

G2 - “Improve the usability of the iPhone.”

G3 - “Create a unique look and style.”

For those two goals, they are certainly achievable. It’s well within Apple’s power to manufacture and develop the product in line with those goals.

As for measurable, at first glance the metrics aren’t as clear-cut as with their long-term goal. Reading between the lines, you can start to see how you might measure them. For G2 you could run usability tests, observing people using the phone and conducting surveys. For G3 you can simply compare and contrast the iPhone with other smartphones in the market.

Also note that while G1 is more long-term, G2 and G3 are short-term goals, to be achieved before launch.

These goals would help Apple to work towards fulfillment of their original vision for the iPhone. They are concrete objectives which are both achievable and measurable.

Planning Your Actions

In order to achieve your goals, there are certain tasks that need to be completed. These are your actions.

Clearly, your actions are intrinsically linked to your goals. You discern your actions from your goals, and you achieve your goals through your actions.

If you haven’t yet thought of your goals, then you should do so now. You can’t possibly come up with a plan of action if you don’t have a goal in mind.

In the previous section, it became apparent that goals are both achievable and measurable. Those two attributes lend themselves to the associated actions.

To figure out what actions you need to take, you need to dissect your goals and understand how to work towards them.

These actions need to be practical tasks you can carry out in order to achieve the goal. Some goals may even require several different actions.

To return to the iPhone example; the goals they set were:

G1 - “Corner 50% of the smartphone market.”

G2 - “Improve the usability of the iPhone.”

G3 - “Create a unique look and style.”

For clarity, let’s take each goal at a time.

For G1, it would seem there are a lot of actions required for to achieve this. That makes sense with such a large-scale, long-term goal. To corner so much of the smartphone market, Apple would have to pull off a lot.

There are various actions that tie in with G1 but when you boil the goal down, the underlying idea is to sell more phones. Perhaps the most obvious way to do that would be to create compelling marketing and advertising campaigns which educate the public on why the iPhone is better than any alternative.

There’s our action for G1:

A1 - “Create marketing campaigns and educate public of iPhone benefits.”

Next up, we have G2. This is a more short-term goal and directly impacts product development. The usability of the iPhone is important to Apple, especially if it wants to fulfill its product vision.

The underlying idea behind this goal is defined in the goal itself: increase usability. There are a number of ways in which usability of a product can be improved that we don’t need to go into here. Let’s assume that for this particular product, the best way to improve usability would be to gather feedback from beta testers, observing how they use the phone and any issues they have, and then refining the UI and UX using that data.

We now have an action for G2:

A2 - “Run beta tests and make UI/UX tweaks based on the data.”

Finally, we have G3. Once more, this is a product oriented short-term goal. According to their product vision, Apple want their iPhone to stand out from the crowd. They want something that looks sleek and stylish, and ultimately, cool.

To achieve this goal, Apple would need to turn to competitor research to see what other smartphones look like. They could then have their designers create something which differentiates them from their competition, while staying in line with other Apple products.

So the action for G3 is:

A3 - “Research competition and create a design which veers away from them.”

It’s worth noting that the actions presented here are specific to each goal, but still relatively general. Take A1 for example. Creating a marketing campaign isn’t as simple as deciding to create a marketing campaign. You need to conduct market research, brief the creatives, produce any advertising materials, and then roll out the campaign.

These chunks are what we call steps. Each action will be comprised of these steps. For the purposes of a product strategy, they can be ignored. When it comes to actually carrying out the action, that’s when the steps come into play.

In the everyday world, an example would be making breakfast. The action is making breakfast. The steps would be choosing a box of cereal, pouring it into a bowl, adding milk, and then grabbing a spoon. But if someone were to ask you what you were doing, you’d tell them you were making breakfast.

Your actions consist of specific steps which you will carry out in order to achieve your goal.

Summary

To best summarize, let’s apply the example of Apple to our strategy funnel.

You can see from the funnel how the vision, goals, and actions we came up with for the iPhone all come together to build up the overall product strategy.

You start by honing your vision. The people responsible for this, commonly C-Level and VP of Product, should meet to discuss their answers to the three key questions. In smaller companies, you might have input from all of the different teams.

Then, you set your goals. These will be a natural progression of your vision and will either come from leadership or come from the product team itself, depending on the structure of your organization. Your goals should be achievable and measurable.

Finally, you need to figure out your actions. These are tasks you will carry out in order to achieve your goals and will generally follow logically from the goals you’ve already set.

There you have it. You now understand the three components of a product strategy, and even better, you know how to create your own.

Thanks for reading, and happy strategizing!